Movie Blog: 'Gone Girl,' The Date Movie From Hell

[NOTE: It is almost impossible to discuss Gone Girl without straying into spoiler territory. If you haven't seen the film — or read the book, for that matter — and don't wish to have sensitive plot points revealed, do not read this review until after you've watched the movie.]

A colleague of mine noted that David Fincher's new film Gone Girl completes a trilogy of sorts detailing male-female relationships gone awry (or, perhaps in the case of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, relationships that start at "awry"). Whereas his Facebook epic The Social Network used Mark Zuckerberg's rejection by the object of his desire as a jumping off point for the creation of the platform that forever changed the way plugged-in humans relate to one another, and Dragon Tattoo engendered hardly any hope whatsoever in the viability of heterosexual couplings, Gone Girl opens with what on the surface appears to be the most enviably normal marriage imaginable. And, with a lot of help from Rosamund Pike's multifaceted performance in the title role, it then spends two and a half hours ripping all illusions in two.

Adapted from Gillian Flynn's best-selling page turner by the author herself, Gone Girl stars Ben Affleck as Nick Dunne, a gallant-jawed goofus who muses, while stroking his wife Amy's hair in the opening shot, about wanting to crack open that girl's skull in order to see what she's thinking. Though Nick's narration indicates violent thoughts, it's worth noting that the Downy fresh image is one of the few in the entire film that cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth doesn't filter down into that trademark jaundiced, sickening yellow pallor. It introduces Amy, who looks directly into Nick's (and the audience's) eyes, as an angelic paragon of domestic bliss. And then the movie brusquely takes her away.

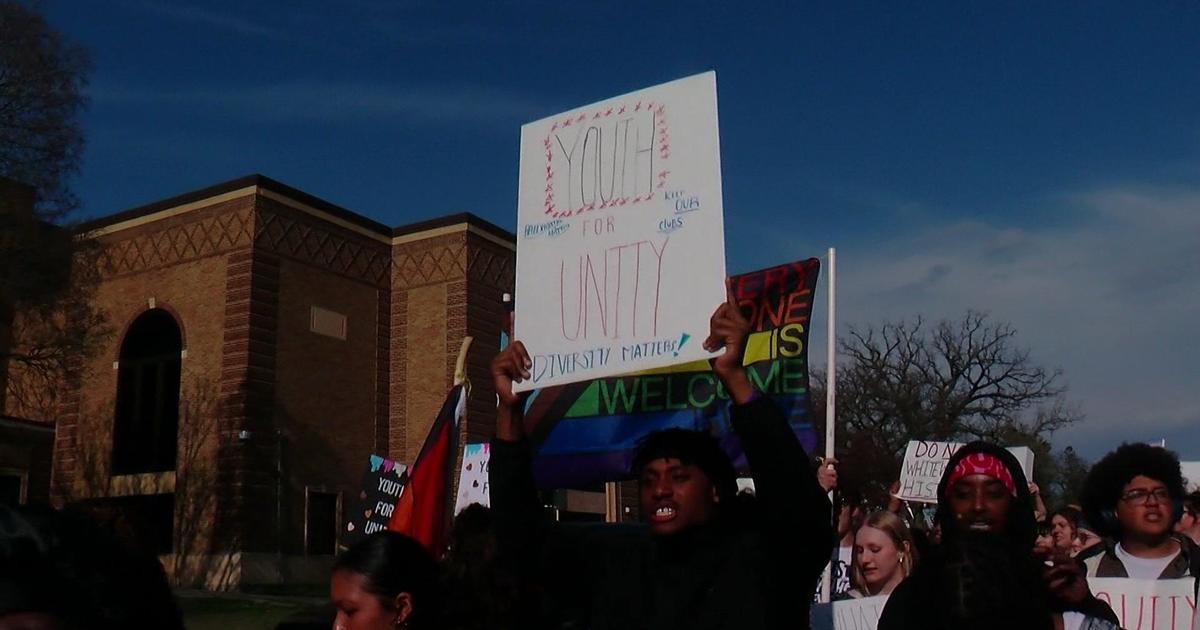

Nick returns to his Missouri home on his and Amy's fifth anniversary and finds his wife has disappeared and all that remains is what seems to be evidence of a struggle. Detective Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens) arrives with a pad of Post-It Notes and suddenly their house is a crime scene. Amy's brittle, snobbish parents arrive from New York City and, with very little time having elapsed, the investigation and the media's exploding coverage thereof take a decided turn against Nick, who is portrayed (and very well may be, as Fincher and Affleck jointly paint him) as a narcissist, a leech, a bum. But is he a murderer?

Meanwhile, as this story is unfolding, Fincher and Flynn routinely flash back the courtship of Nick and Amy — who tellingly hyphenates her surname Elliot-Dunne — as told through her diary entries. The story the flashbacks tell offers a stark counterpoint to Nick's own defenses. And then, at roughly the same reel change as that infamous gear shift in Hitchcock's Psycho, Gone Girl drops the bombshell that hooked so many readers.

And the weird thing is … it's not by a massive stretch any weirder than the human behavior the film depicted up to that point: the media circus, the search party groupies asking for selfies with Nick, the palpable tension between the in-laws who otherwise seem to want the same thing. But the hard left turn the plot takes is more of an abstraction. Gone Girl's central point argues that the baseline insanity existing in every relationship is the extent to which everyone who enters one tries to alter their identity to adhere to what they think their relationship demands of them. The same goes for the working relationship between the movie's director and screenwriter. Here, the fastidious Fincher's marriage to Flynn's melodramatic, cynical, bloody abandon produces a far more ferocious synthesis of the uneasy balance between cold professionalism and pulp sensationalism that marked Fincher's last two films. Here, it spills out into open psychological anarchy. See it with someone you don't love.