Investigation Into Man's Death Reveals Depth Of Minnesota's Prescription Drug Problem

MINNEAPOLIS (WCCO) -- A Twin Cities family wants answers after they believe a psychiatrist went too far in prescribing medications to their son and brother.

Mike Arens died 18 months ago. WCCO found the doctor writing his prescriptions has been in trouble before.

WCCO investigates the psychiatrist who's been on the state's radar for decades and the upcoming changes to better track what medications Minnesotans take.

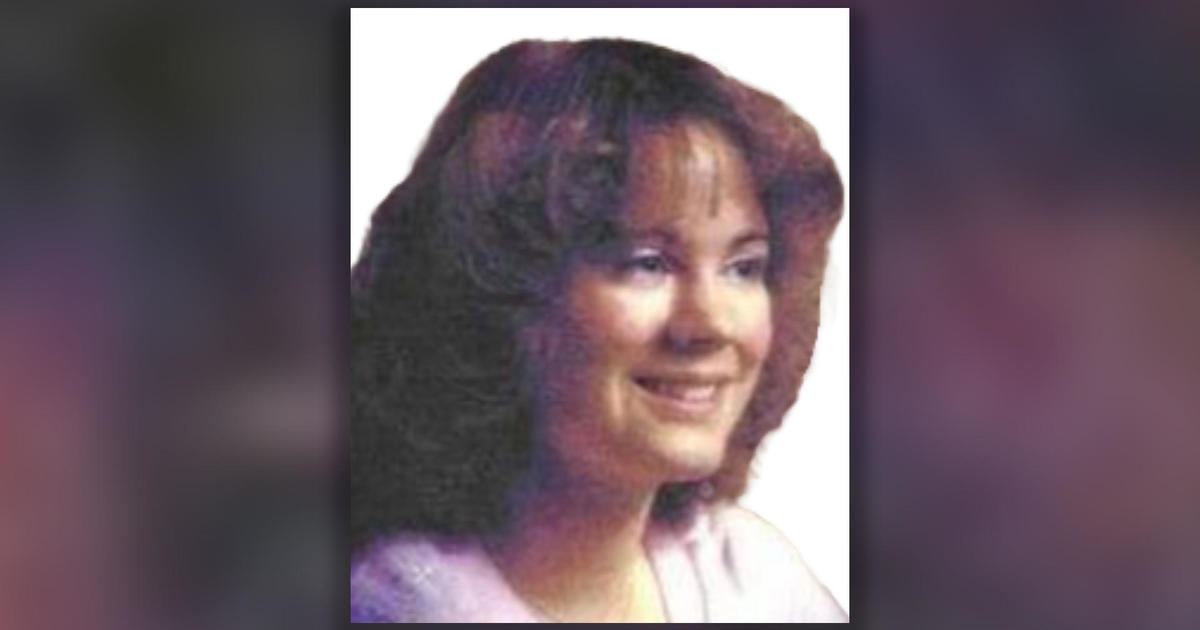

Known for his generosity and signature smile, Mike Arens grew up the middle boy and a three-sport athlete in a tightknit family.

It's now Mike's baby brother, John, who's left to wonder how they got here in a few short years.

"Mike had a huge heart," John Arens said.

"We were typical siblings where we played together and fought together and grew up together," he added.

After graduating from Eden Prairie High School, Mike went on to build one of the most successful window cleaning companies in the Twin Cities. But years of climbing ladders and weight-lifting took their toll. Arens had hip surgery in 2011 at the age of 50.

"I think that's when his pain addiction started," John Arens said.

"I think any family is susceptible to it and it started out very innocently enough," he said.

His family had their suspicions, he'd be up all night, sleep during the day, and go days without answering his phone. All as his business started to take a dive.

"Mike was stubborn and head strong that he didn't have a problem and whatever problem he did have he could fix on his own," Arens said.

Finally, three years into his pill addiction, his parents and siblings staged an intervention. Arens told them he didn't need any help.

"The doctor that was involved in the intervention promised us that Mike would not make it, he would die. He expected Mike to die within a year and he was right," Arens said.

A friend found Mike Arens dead in his Bloomington home in October 2015. His autopsy revealed he had heart disease and a "history of multisubstance dependence" -- leaving his family to piece together how it started.

"I can't imagine how someone couldn't become an addict with that much opportunity," Arens said.

Inside Arens' house, they found hundreds of empty pill bottles once filled with dozens of different types of prescription drugs.

When they looked closer, one doctor's name appeared again and again.

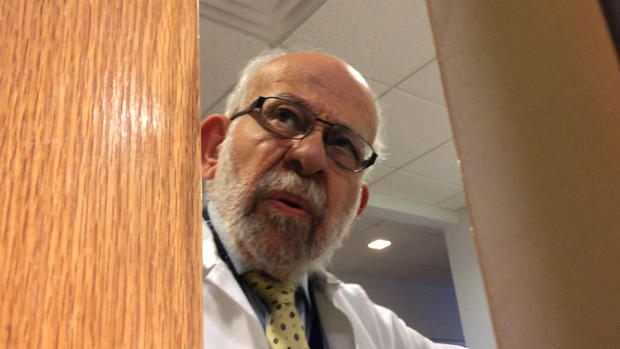

Dr. Faruk Abuzzahab is an 85-year-old licensed psychiatrist. He's practiced for more than 50 years, currently out of this clinic on Lake Street in Minneapolis.

Dr. Abuzzahab told us HIPAA prevented him for talking about Arens' case. But, WCCO discovered the doctor has been surrounded by controversy and complaints for decades.

Once a psychiatry professor at the University of Minnesota, Dr. Abuzzahab took a woman off her medication for schizophrenia as part of a drug study. She committed suicide days later.

In its investigation, the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice would suspend his license for seven months as discipline for "the disregard for the welfare of 46 patients, five of whom died in his care shortly afterward."

In his latest complaint, the board found the doctor "prescribed excessive quantities of medications for multiple patients."

That investigation revealed in "seven cases Abuzzahab's prescribing practices and procedures failed to meet the minimum standards."

"We fully recognize that, that Mike was an addict but he needed help," John Arens said.

WCCO found Dr. Abuzzahab prescribed Arens at least eight medications, mostly for psychiatric problems like anxiety and ADD and the doctor made decisions for him that his family considered reckless.

Arens got three DWIs in just two weeks for driving high on medications back in 2013. Dr. Abuzzahab wrote a letter to the state to help him get his license back saying Mike is fine to drive "provided he has passed the eye exam, written and road driving test."

"Mike must have been driving in a state of intoxication for years. He was a danger to himself and others," John Arens said.

The Executive Director of the Board of Pharmacy, Cody Wiberg, examined Arens' prescription records for WCCO. While there is no evidence the drugs the doctor prescribed played a direct role in Arens' heart disease or death, Wiberg questioned why the psychiatrist would write him a prescription for tramadol, an opioid medication used to treat severe pain.

"Minnesota is really in the grips of an opioid abuse and overdose epidemic," Wiberg said.

Wiberg acknowledged it is not uncommon for someone recovering from an injury such as Arens' hip surgery to get addicted because of the drug's power.

The state is trying to do a better job tracking prescriptions to flag patients who doctor shop to get multiple prescriptions in short periods of time. Under the current prescription monitoring program, every pharmacy must record that information in a database each day. But, on July 1, every physician will also need an account. But they won't be required to use it. Right now, just 40 percent of doctors do.

In Mike Arens' case, WCCO found at least five other doctors did write him prescriptions. But because the prescription monitoring program isn't required -- we don't know if Dr. Abuzzahab knew that or not.

"Ultimately it is going to have to be the pharmacist and the prescribers that are actually taking care of patients that are going to have to use the tools that we make available to them," Wiberg said.

Arens' family made a formal complaint to the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice about his care, more than a year ago. They have yet to hear anything back.

The board's executive director declined WCCO's repeated requests to be interviewed.

"We felt helpless and we continue to feel helpless because of the lack of accountability. Somebody should be monitoring the drugs that are given out to our loved ones," Arens said.

Liz says of the 8 million prescriptions filled each year in Minnesota, more than 3 million are for opioids. Under proposed guidelines, doctors would not be allowed to see patients on state health care programs if they keep prescribing too many painkillers.